“That third idea, that we will never have to be alone, is central to changing our psyches. It’s shaping a new way of being. The best way to describe it is ‘I share, therefore, I am.’ … We slip into thinking that always being connected is going to make us feel less alone. But we are at risk, because the opposite is true. If we are not able to be alone, then we are only going to know how to be lonely.”

But the notion that there is a proper and responsible way to become or to be a foreign correspondent — go to journalism school, get a lowly reporter job, work your way diligently up the ladder, take risks only backed by robust institutional support — and that all others are recklessly irresponsible, if not illegitimate, is simply to deny reality.

Read more here: National Post – Chris Selley – Amanda Lindhout and Her Critics

15 to Life Doc Trailer

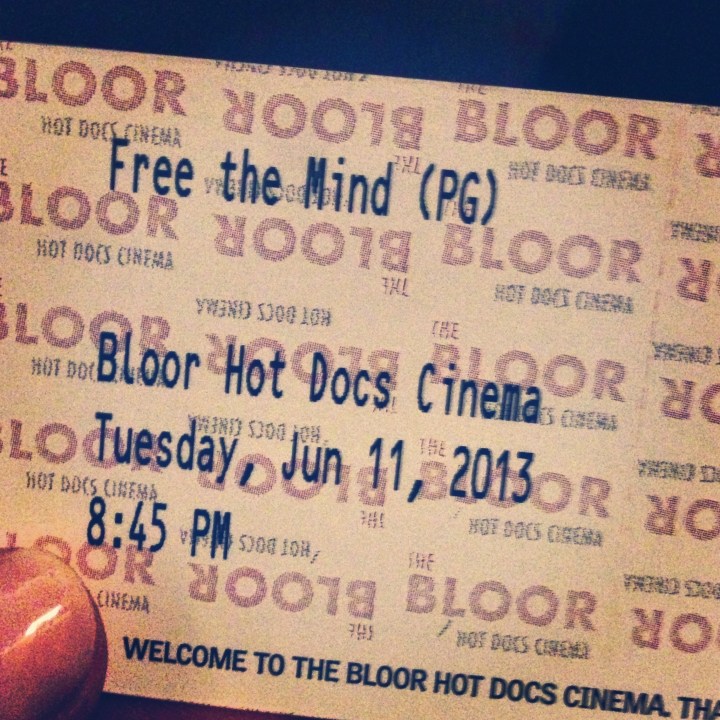

31 ticket stubs later

Needless to say, I took full advantage of my conference pass at this year’s Hot Docs festival. Here’s a list of the films I saw:

- The Manor

- The Human Scale

- Terms and Conditions May Apply

- I Am Breathing

- Estela/Who Is Dayani Cristal?

- Valentine Road

- In the Shadow of the Sun

- The Exhibition

- Happy Birthday Emily/Furever

- The Only Son

- Tough Bond

- Tales From The Organ Trade

- Like A Breath/Remote Area Medical

- NCR: Not Criminally Responsible

- Blood Brother

- In Saint-Sauveur/Dead or Alive

- Alphee of the Stars

- American Commune

- Here One Day

- Blackfish

- God Loves Uganda

- Declaration of War/The Kill Team

- The Barrel/Menstrual Man

- The Great Hip Hop Hoax

- Anita

- Pussy Riot – A Punk Prayer

- A Whole Lott More

- Fight Like Soldiers, Die Like Children

- Maidentrip

- I Will Be Murdered

- 10 Reasons to Live

What were your favourites?

Africa and Film

Some of the crews at Kwita Izina 2012, the gorilla naming ceremony in Rwanda.

I’ve been working at Hot Docs as an Industry Programs Intern for a few weeks now. One of the most exciting projects I’ve been working on is their Blue Ice Group Documentary Fund for African filmmakers, which you can read more about here. The fund helps some amazing projects, and it is so exciting to read about all of the interesting documentary work going on in various African countries.

Recently, I read an article about the opening of the first cinema in Rwanda. I remember living in Kigali last summer and needing a taste of home. I thought it would be a nice treat to take myself to a movie. To my dismay, when I tried to find movie listings, I learned that there wasn’t a movie theatre in all of Rwanda (first world problems, I know).

My roommates and I went for dinner one night to a restaurant that, to celebrate Canada (I can’t remember if it was actually Canada Day, or not), had hung up a screen and showcased Goon – not exactly the best representative for Canadian film, but hey, they had popcorn, and Eugene Levy does make an appearance.

That was also the summer that The Dark Knight premiered, and two of my roommates seriously considered bussing to Kampala, Uganda, to see it.

What got me thinking about the Blue Ice Fund and the lack of theatres in Rwanda is an article I read recently called the Rise and Rise of African Films. Starting with an interesting summary of the history of filmmaking in Africa, the article brought up some good points:

“The slow growth of African film is now in fast forward thanks to new technology. With digital media, filmmakers are no longer reliant on expensive 35 mm film. Production costs are becoming affordable, enabling a flow of content with transnational themes that could reach out to international audiences… International links are boosting training. In East Africa, the International Emerging Film Talent Association partners with Ethiopian Film Initiative to train new directors. In Rwanda, filmmaker Eric Kabera founded the Rwanda film school and Rwanda Film Festival (Hillywood), which shows films on inflatable screens around the country.”

It’s interesting to see how funding and issues of accessibility are being addressed in regards to developing and supporting film communities in Africa, especially as I have been thinking a lot lately about accessibility to the film world here in Canada.

At the end of the day, I’m incredibly excited to see what the future brings for filmmakers both in African countries and in my own community, especially for the projects that I have been exposed to this summer.

Couldn’t stay away!

Sometimes we need a reminder to slow down

“The problem with accepting — with preferring — diminished substitutes is that over time, we, too, become diminished substitutes. People who become used to saying little become used to feeling little…

We live in a world made up more of story than stuff. We are creatures of memory more than reminders, of love more than likes. Being attentive to the needs of others might not be the point of life, but it is the work of life. It can be messy, and painful, and almost impossibly difficult. But it is not something we give. It is what we get in exchange for having to die.”

Read more here: How Not To Be Alone.

Is filmmaking accessible?

My experience at the 2013 Hot Docs Film Festival and Doc Accelerator program was incredible. I learned a lot, and attended workshops that I otherwise would not have been able to afford. However, one thing did stick out in the back of my mind throughout the festival: how do issues of accessibility and class relate to the film industry?

I certainly acknowledge my own privilege in my goals to enter the film industry. Not only was I incredibly lucky to be chosen to take part in the Accelerator program, but I am also lucky to own a smart phone, laptop, and decent camera – the 3 things you really need to market yourself and start a passion project.

It seems to me that the only way to break into the film industry is to just do it. I must have heard “just do it” a hundred times. And fair enough. ‘Just doing it’ shows initiative, drive, and determination. It means you’re here to stay, and it’s your way of paying your dues and earning a place among the greats.

But what does “just do it” actually mean in terms of accessibility? Is it fair to assume that we all begin at the same starting point?

Of course not.

Some of the factors that jumped into my head: student debt and the obscene cost of living in any urban city with a film community.

It made me a bit sad to hear this conservative ideological rhetoric of ‘just do it and work hard enough until you succeed’ be so prevalent in the left-leaning arena of filmmaking and storytelling. In present day, it doesn’t matter if you have initiative, drive, and determination if you can’t afford the technology necessary to ‘just do it.’

One of the speakers I had the opportunity of listening to joked that us Canadian artists were too used to being supported by government grants, that now that these funds no longer exist, we don’t know how to adapt. It was true; I hadn’t really sat down and thought about these cuts to arts funding until I decided to aspire to be a documentary filmmaker (selfish, I know).

This made me think a lot about values, culture, and art. Take the Vancouver olympics, for example. The mascots, medals, and celebrations are used to exemplify the host country’s culture. All of the 2010 items embodied indigenous visual art, dance, literature, and imagery. This shows that art gives us life, and we indulge in this to celebrate. Why is it that we refuse to invest in what we define ourselves by?

And if art is unaccessible, who gets to define who we are?

It is horrifying to think that the arts, with all of the countless benefits, can be used by the rich to exploit the poor. This is not a new concept. You see it in instances like the Vancouver olympics, and you see it in documentary filmmaking.

For example, quite a few films I saw at this year’s festival (while absolutely beautiful, in both story and visuals), did possess a bit of a white saviour complex or romanticism of the developing world. What does the telling of these stories mean for the host communities once the cameras are turned off? What happens after a piece of art is created, to those who are used to create it?

My best attempt is to start at the beginning: with the filmmakers. I recognize that I am no exception to this cycle. I still want to be a filmmaker. No, I don’t have the best camera, but I do have something I can use to get started, which is more than a lot of other people.

However, if more people could control the production of artistic content, then a higher number of opinions, standpoints, and experiences can be more authentically integrated into not only the artistic definition of a time and place in history, but also to the future of these societies.

One of the most important things I learned in grad school was the power of listening and taking a step back. How do we do that as filmmakers, especially when for those who have a head start? How can anyone become a filmmaker? How do we make filmmaking a viable dream for anyone?

One solution I learned about was film co-ops, where you can pay a small membership fee to access film equipment. An example of these is LIFT (Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto).

While I still don’t know much about them, perhaps this is one way we can increase access to expensive equipment that serves as the biggest barrier to filmmaking.

The Most Haunting Photo From Bangladesh

The Most Haunting Photo From Bangladesh

“Every time I look back to this photo, I feel uncomfortable — it haunts me. It’s as if they are saying to me, we are not a number — not only cheap labor and cheap lives. We are human beings like you. Our life is precious like yours, and our dreams are precious too.”