I read an article before leaving for Rwanda that stated people become more conservative as they age.

I laughed when I read that.

Personally, I couldn’t see myself, or at least my values, changing that much. I understand that as you undertake more responsibilities – a mortgage, a family, car payments, saving for retirement – you become more protective of your money and possessions.

You become, well, more responsible.

I’m not saying I’m not responsible, but I’ve always believed that fun can still exist in taking calculated risks. However, as I read on, I still couldn’t imagine myself becoming that uptight, or my dreams straying far from what they have always been: to travel to every country in the world, to explore, to be spontaneous, to tell stories.

To invest in adventure.

I have always loved to travel. I can usually be found looking for flights to plan my next trip, packing in as much as possible and trying to see all the surrounding countries from where the plane would land.

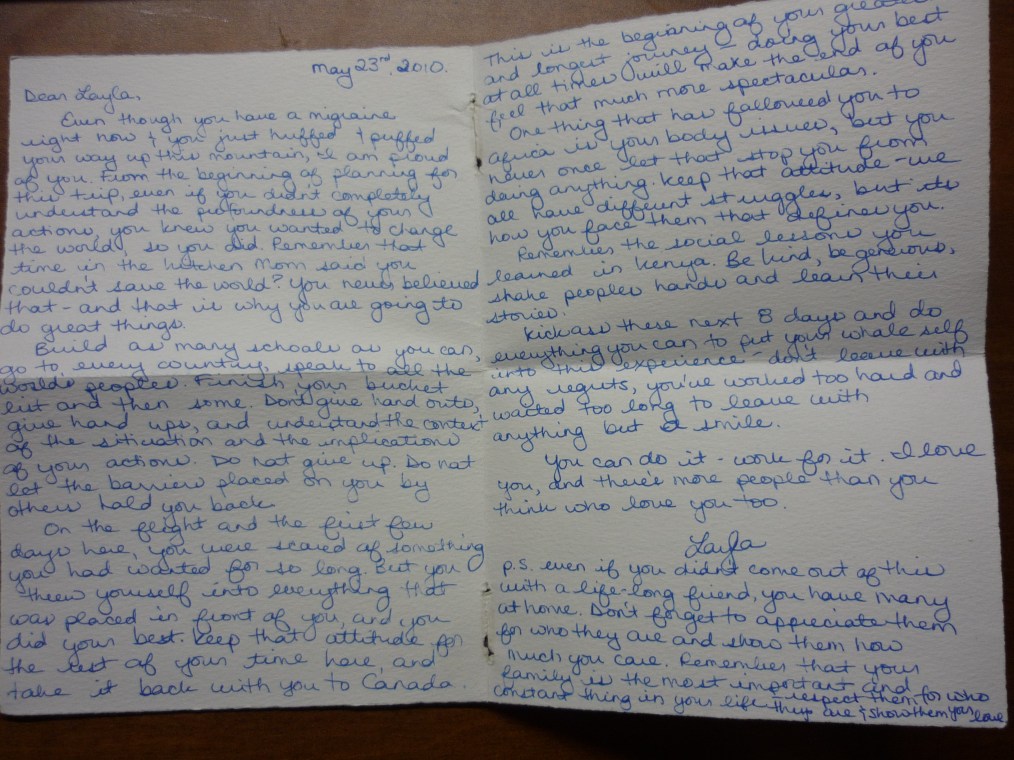

After my first few days in Rwanda, the shift from reckless adventure to conservatism is something I haven’t been able to get out of my mind, and is something that has contributed greatly to my initial anxiety. It is something I am definitely struggling with.

It is hard to explain how stressful traveling is, especially with valuable equipment that, as a student, I could not afford to replace if it were stolen.

This stress is exhausting, but it also makes you feel like a privileged western troll whose main concern is guarding its precious treasures.

I have been polite, enthusiastic and energetic, but I don’t like how I have been thinking. I do not feel like the unafraid, excited, and adventurous journalist I have always believed I was.

Because I do not completely trust leaving anything at home, and because there is nowhere to lock my pelican case in my room (which I brought two cables and two padlocks for), I’m trying to keep my laptop, camera, travel documents and passports in addition to anything else I need for work, with me at all times.

Yes, my arms will probably be jacked after this trip, but to be on constant watch of where your bag is, to sound whiney, is kind of annoying.

To be skeptical of my surroundings, especially in a developing and proud country, and considering that I am incredibly lucky to even be able to afford any of this equipment, makes me feel like a total prick. The kindness and generosity of my landlord, his family, the staff of both our home and our work, all of whom I do trust, heighten these feelings of guilt.

However, we have been warned by many people to still take precautions regardless of who is around. After all, once it’s gone, it’s gone, and you’re a pretty useless journalist without it.

This trip is certainly a reminder of what is important, and what you really need to survive, be happy, or do your job. Packing was the first step; limited to a certain weight, your luggage is only filled with the bare necessities. Plus, you’re carrying it all, so you want to ensure you travel light.

And of course, as with any expensive trip, and as a student, I must be somewhat conservative with my money to make sure I can make it through to the end with enough to eat and a place to sleep.

But I haven’t figured out how to balance adventure and work without risking losing it all, or losing valuable cultural experiences.

What is scaring me the most, so far, is that I doubt ever doing another professional trip like this again.

It is different to travel as a tourist, and I would argue much easier. For example, tourists don’t usually stay in one place for two months. Having to live abroad requires more equipment and more packing, which means there is more to lose.

I’m worried that perhaps the article I read was right. Maybe as we grow up and embark on our own adventures we learn that it really isn’t as simple as buying a plane ticket and getting to the airport on time.

Maybe our dreams weren’t as simple, or realistic, as we thought.

There is careful planning involved, months of preparation, and many costs, including travel outside of the airfare, accommodations, and utilities, all of which are also being paid at home and going unused.

I hate that I’ve been thinking like this. I want to go back to being an adventurer, as naïve as it was.

But I don’t think I can, and that scares me.